In the broad current of the revolutionary movement, very few remain truly “unknown” within the larger public sphere. Because of the leadership responsibilities they assume, or the roles they play in various struggles, the names of most activists gradually become familiar to the outside world. In today’s terms, one might say they receive a certain amount of media visibility. When they sacrifice their lives in the course of the movement, even if not their entire history, at least a significant part of it becomes known to the public.

But the revolutionary movement also contains sacrifices that remain unseen. These are sacrifices made without acquiring any public recognition, without becoming known to the people, and without leaving behind a name. Yet, these sacrifices too endure permanently in the history of the revolution. Strictly speaking, theirs is an even more selfless form of sacrifice. They are the unsung heroes.

Among such exemplary individuals was Comrade Thota Seetharamaiah. He passed away on December 8, 2025, due to ill health. He must have been around 65 at the time of his death. His native village was Chintarelu, in Aswapuram Mandal of today’s Bhadradri Kothagudem district. While studying for a degree in Chirala, he worked for some time in the RSU and became a full-time activist of the revolutionary movement in 1980. For a while, he worked at the Peace Book Centre, distributing revolutionary literature. At that time, everyone referred to him as “PBC Kumar.” By 1985, because of state repression, the Peace Book Centre had to be shut down, forcing him to go underground. During that period he worked as a courier.

Having learned computer operations, DTP, and offset printing, he handled the responsibility of printing revolutionary literature and transporting it to various movement areas. What else he did during those fifteen years is not publicly known, but from 2001 onward his work shifted primarily to Dandakaranya. From that point, he served as the computer operator and the most trusted assistant of the Party’s General Secretary, Ganapathy. Among the cadres of Dandakaranya, he became widely known as “Computer Anandanna”—so central was the computer to his identity that it virtually became his surname.

He spoke little, observed much, and worked tirelessly, sitting for long hours before the computer without the slightest sign of fatigue. As part of his responsibilities, he accompanied Ganapathy to different states and districts, thereby becoming familiar to revolutionary leaders across the country. During higher committee meetings, he often had to work day and night. Yet he always remained cheerful, greeting central and state committee members with a smile while preparing printouts, copying files, and typing resolutions. In Dandakaranya, he taught many junior comrades DTP work. Whenever any comrade’s computer developed a problem, he was the one who repaired it. It is no exaggeration to say that exhaustion, boredom, and rest were words absent from his dictionary.

By the time he entered Dandakaranya, he was already in his forties and, with his graying hair, looked slightly older than his age. Wherever he went, comrades naturally stood by him as companions and helpers. During journeys from one area to another, they would voluntarily carry his computer and other belongings. But he never sought any special treatment, always trying to manage his own tasks. Even so, comrades often insisted and simply took the luggage off his shoulders.

Though he did not know Gondi well, the way he mixed Telugu, Hindi, Gondi, and English into a charming “khichdi” amused the cadres. Through this multilingual mix, he interacted with them constantly, filling the guerrilla camps with laughter.

As for his work, accuracy and speed were his hallmark. Any document he typed required correction only on very rare occasions. When Ganapathy or other central leaders dictated something urgently, he typed with remarkable speed. Discipline was another major quality of his. As the assistant to the General Secretary, it was natural that he came across internal matters of committees, debates, and disagreements. But he never mentioned them anywhere; he maintained strict confidentiality.

Although he had limited interaction with Adivasi masses, he built excellent relationships with Adivasi cadres. In fact, more than senior leaders, he spent most of his free time chatting with lower-level cadres. In the guerrilla camps, he was the one who screened films at night; cadres would approach him in advance, negotiate which films they wanted to watch, and he would oblige. Thus he maintained many such “secret understandings” with them.

In political discussions, he spoke briefly and directly, expressing his views without hesitation. He never participated in conversations he found unnecessary. Most remarkable was his memory. He could instantly locate any file, article, or resolution—down to the drive and folder it was stored in. Everyone praised him for having a “computer brain.” By promptly providing all reference articles and resolutions required by then General Secretary Ganapathy, the martyred leaders Namballa Kesava Rao and Cherukuri Rajkumar, and many others, he became an invaluable support to them and, in turn, made an extraordinary contribution to the revolutionary movement.

By the time he came out for medical treatment in 2023 and was arrested, he was suffering not only from other health problems but also from Alzheimer’s disease. Even in police custody, he reportedly said anxiously, “Look… the police are coming… come, let’s vacate the camp and move.” After he was released on bail, his family arranged a helper who assisted him with meals, bathing, and daily needs. When a friend visited him in May this year, he appeared physically fine though his memory had not improved. During that visit, the friend casually mentioned “Red Army” and “White Army.” Immediately he responded, “Yes… Red Army… I will not surrender… I will not surrender.” Even in a state where he could not understand where he was or who surrounded him, some fundamental convictions seemed to remain deeply lodged in some corner of his mind—fragments of memory that even Alzheimer’s could not erase.

In the present historical moment—when counterrevolutionary tendencies parade shamelessly and disgustingly in the lap of the state, distorting fundamental principles and placing the revolutionary movement in grave danger—it becomes profoundly necessary to remember and honour comrades like Thota Seetharamaiah, who considered the revolution their very life and offered their entire being to it. Their sacrifices must be acknowledged with deep respect.

- Urmila

పాట్నా జైలులో CPI(మావోయిస్టు) పోలిట్బ్యూరో సభ్యుడు ప్రమోద్ మిశ్రా ఆమరణ నిరాహార దీక్ష

పాట్నా జైలులో CPI(మావోయిస్టు) పోలిట్బ్యూరో సభ్యుడు ప్రమోద్ మిశ్రా ఆమరణ నిరాహార దీక్ష  ‘అప్రతిహత’ విప్లవ గాథ – ముసాఫిర్

‘అప్రతిహత’ విప్లవ గాథ – ముసాఫిర్  అరెస్టును లొంగుబాటుగా చూపించడంలో మర్మమేంటి?

అరెస్టును లొంగుబాటుగా చూపించడంలో మర్మమేంటి?  తల్లికి మావోయిస్టు పార్టీ నాయకుడు పాక హనుమంతు @ గణేష్ లేఖ

తల్లికి మావోయిస్టు పార్టీ నాయకుడు పాక హనుమంతు @ గణేష్ లేఖ  ఏ మార్గాన్ని అనుసరించాలి?

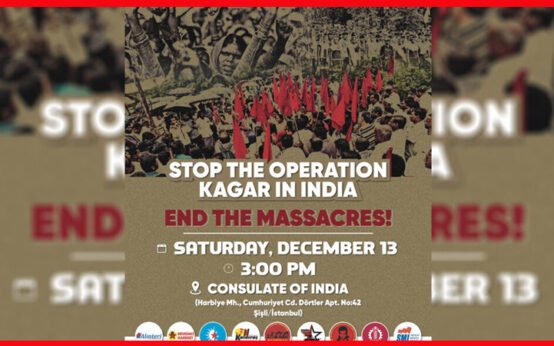

ఏ మార్గాన్ని అనుసరించాలి?  ఆపరేషన్ కగార్ కు వ్యతిరేకంగా జర్మనీ,టర్కీ లలో కార్యక్రమాలు

ఆపరేషన్ కగార్ కు వ్యతిరేకంగా జర్మనీ,టర్కీ లలో కార్యక్రమాలు